John Hilbert, a renowned chess historian, has once again delivered an outstanding article on correspondence chess history for The Campbell Report. This marks his 11th contribution to the platform. You can explore more about John Hilbert by visiting his prior articles available under the ‘On the Square Menu’. Additionally, links to his previous articles are conveniently listed at this page’s end. Plus, you can download the games mentioned in the article in PGN format.

Several of John Hilbert’s pieces on this website have been featured in his award-winning book, “Essays in American Chess History” (Caissa Editions 2002), which clinched the 2002 Cramer and Chess Journalists of America Award for Best Book of the Year. Kudos to John Hilbert for this esteemed accolade from both the Cramer Committee and the CJA.

John Hilbert continues his literary journey with three new books released recently. For enthusiasts of American chess history, here are his latest offerings:

- New York 1940 (Caissa Editions);

- Young Marshall (Publishing House Moravian Chess);

- Walter Penn Shipley: Philadelphia’s Friend of Chess (McFarland).

Staunton’s Telegraphic Chess Revolution

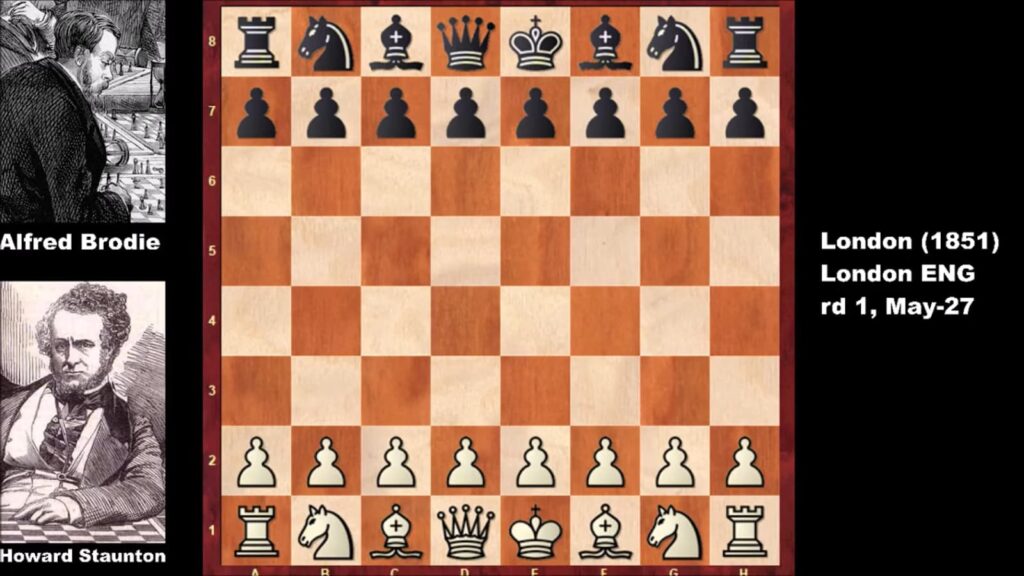

Today’s chess community largely recognizes Howard Staunton (1810-1874) as the sole English world champion and the figure who declined a match against Paul Morphy. However, the vast scope of his contributions to chess often remains obscured by history. Beyond chess, Staunton was a prolific writer. His credentials also boast of a deep dive into Shakespearean studies and a comprehensive 517-page work in 1865 about major English public schools titled, “The Great Schools of England…” which highlights institutions like Eton, Winchester, and Westminster.

- Nearly two decades prior to this, Staunton penned “The Chess-Player’s Handbook” in 1847, which became an essential guide for English-speaking chess players;

- Following this, he released “The Chess-Player’s Companion” and in 1852, he documented the first global chess tournament in “The Chess Tournament”;

- Staunton didn’t just play in this 1851 London tournament, but was a key organizer as well.

An often overlooked aspect of Staunton’s legacy is his consistent contributions to the Illustrated London News. From 1845 till his passing in 1874, Staunton penned weekly columns for this influential paper. Hooper and Whyld, in “The Oxford Companion to Chess”, hail this as Staunton’s most significant journalistic endeavor. Across his tenure, Staunton penned over 1,400 weekly columns. Notably, a good chunk of these delved into correspondence chess, especially the emerging trend of telegraphic chess.

Staunton’s enthusiasm for chess via telegraph was evident early on. As per Hopper and Whyld, the inaugural telegraphic match occurred in 1844, connecting Washington and Baltimore via America’s first telegraph line. Come April 1845, Staunton, alongside Captain Kennedy, journeyed to Gosport to challenge a London quartet in a game of chess via telegraph. This innovative match paved the way for future telegraphic chess matches, highlighting Staunton’s forward-thinking approach to the game.

Telegraphed Moves: 19th Century Chess Innovation

- For those intrigued by the telegraph’s evolution during the 19th century, Tom Standage’s “The Victorian Internet: The Story of the Telegraph and the Early Online Pioneers” (Berkley Books: New York 1998) offers an engaging read;

- While Standage doesn’t delve into the telegraph’s role in chess, he does have a chess-related piece: “The Turk: The Life and Times of the Renowned 18th-Century Chess Machine” (Walker & Company 2002);

- This pairs well with Gerald M. Levitt’s “The Turk, Chess Automaton” (McFarland 2000).

Staunton’s enthusiasm for telegraphic chess wasn’t limited to his matches between London and Gosport. His columns in the Illustrated London News often discussed telegraphed chess events. For instance, in April 1856, he highlighted a telegraphed chess match between Liverpool and Manchester teams. Although the English Telegraph Company had hesitations about dedicating a line for chess matches between London and other major cities, they made an exception for these two. Staunton shared an in-depth account from an observer in Manchester, which had been published in the Manchester Guardian on March 29, 1856. The detailed report underscores the novelty and excitement of telegraphic chess at that time:

A chess consultation game started between Manchester and Liverpool clubs using electric telegraph and began at five in the evening. It was a serious match, but no bets were placed. The players for Manchester included Du Val, Kipping, jun., Cohan, Pindar, and Hasche, while Liverpool was represented by Sparke, Sinclair, Saul, Poeschmann, and Jones. An amusing anecdote: for the first move, due to the distance, Manchester had to guess which hand a Liverpool player held a specific pawn in to decide who would start. The event garnered much interest in both cities. Thanks to the Telegraph Company’s cooperation, clubs were positioned near the wires, allowing a move made in Manchester to be known in Liverpool faster than a messenger could inform other Manchester members. Both clubs opened their doors to the public, and many gathered, tracking the game’s progress on their boards. By eight in the evening, only 11 moves had been played. By one in the morning, after 28 moves and an eight-hour game, both teams agreed on a draw.

Liverpool – Manchester [C50]

Telegraph Game – March 28, 1856

- e4 e5;

- Nf3 Nc6;

- Bc4 Bc5;

- 0-0 Nf6;

- Re1 d6;

- c3 Bb6;

- d4 0-0;

- Bg5 exd4;

- cxd4 Bg4;

- d5 Ne5;

- Nbd2 h6;

- Bh4 Ba5;

- Be2 Ng6;

- Bxf6 Qxf6;

- Rb1 Bxf3;

- Bxf3 Ne5;

- Be2 Qf4;

- b4 Bb6;

- Rf1 f5;

- g3 Qg5;

- Kg2 f4;

- Nf3 Nxf3;

- Bxf3 Rf6;

- h4 Qe5;

- g4 a5;

- b5 Bc5;

- a4 Kf7;

- Qe2 Ke7.

Interestingly, as documented by Hooper and Whyld in The Oxford Companion to Chess under the entry for “telegraph chess,” a unique historical chess event occurred in 1858. At that time, Howard Staunton challenged Paul Morphy to a game of chess via the newly established transatlantic cable. Fortunately for Morphy, he had already departed for England when the challenge arrived, as the cable failed after just a month and was not successfully replaced until 1866. This anecdote highlights the early challenges faced in connecting England and the United States through telegraph wires, but more reliable methods would eventually emerge. It’s worth noting that such technical difficulties did not affect telegraph chess games conducted over land.

Over the years, the novelty of playing chess via telegraph gradually diminished, but Staunton continued to occasionally publish these games and even provided annotations for some of them. In May 1863, during the midst of the Civil War in the United States, Canadian chess players used telegraph connections to engage in a mock chess battle. Staunton introduced the following game to his readers: “The following exciting match was played by telegraph a few weeks ago between the Chess Clubs of Hamilton and St. Catherine’s in Canada West.” The game, originally published with Hamilton playing Black, has been converted into standard form with Hamilton playing White:

Hamilton – St Catherine’s [C51]

Canadian Telegraph Game – April 1863

- e4 e5;

- Nf3 Nc6;

- Bc4 Bc5;

- b4 Bxb4;

- c3 Bc5;

- 0-0 h6 (This move is not advisable as it wastes precious time when both players are under time pressure. Playing 6…d6 would have been a better choice.);

- d4 exd4;

- cxd4 Bb6;

- Qb3 Qe7 (Once again, Black squanders valuable time. They should have immediately moved their Queen to f6.);

- Ba3 Na5 (This counter-attack does not prove as effective as anticipated, although St. Catherine’s players may not have had a better option.);

- Qa4 Qf6;

- e5 Qd8 (With no good moves left, Black’s retreat with 12…Qh5 would have been a less damaging choice.).

This historic telegraph chess match showcases the challenges and decisions faced by players in a unique and time-sensitive context.

Boston – Springfield [Unknown Source]

Telegraph Game

- e6 (This is the decisive game move. Whether Black captures this critical pawn or leaves it be, the result is a hopelessly shattered and vulnerable position.);

- fxe6;

- Bxe6 Nc6;

- Bxg8 Rxg8;

- d5 Qf6 (Had Black moved the knight, mate would have swiftly followed in a few moves.);

- Re1+ Kd8;

- dxc6 d6 (Evidently, capturing the rook with Be7+ and Bf6+ would have resulted in losing their Queen.);

- Nbd2 g5 (Given that the game was already lost, there was nothing to lose by playing this move.);

- Nc4 Bxf2+ (As good a move as any, and they could have followed it with a Queen sacrifice; the outcome would have been the same.);

- Kxf2 g4;

- Nxd6 cxd6 (Had they taken the other Knight with the pawn, White could have mated them in three or four moves.);

- c7+ Kxc7;

- Qc4+ Kb8;

- Rac1 Qd8;

- Qxg8 (1-0).

Unlike the other games in this collection, this particular game is found in Mega Corr2, Tim Harding’s comprehensive correspondence chess database, although its source is unknown. It is likely that Staunton also obtained the game score from another publication, possibly of American origin, but he does not provide a specific source. Staunton simply mentions that “The following is one of two Games lately played, by telegraph, between the Clubs of Boston and Springfield, United States.” In this case, the game has been presented with White making the first move.

Boston – Springfield [C51]

Telegraph Game – Early 1869

- e4 e5;

- Nf3 Nc6;

- Bc4 Bc5;

- b4 Bxb4;

- c3 Bc5;

- 0-0 d6;

- d4 exd4;

- cxd4 Bb6;

- Nc3 Bg4;

- Bb5 Bxf3;

- gxf3 Kf8;

- Ne2 Qf6;

- Bxc6 bxc6;

- f4 c5;

- e5 dxe5;

- dxe5 Qe6;

- Ng3 h5;

- Qf3 Re8;

- Bb2 Qh3;

- Qe4.

20…Nh6 (Many would have preferred playing 20…h4, with an eye on the continuation 20…h4 21.Nf5 Nf6, but if White then responds with 22.Qg2, the counter-attack does not lead to much.)

21. a4 Ng4

- Qh1 c4;

- Ra3 Rd8;

- Rf3 h4;

- Ne4 Qxf1+;

- Kxf1 Rd1+;

- Kg2 Rxh1;

- Kxh1 Rh6;

- Kg2 Rc6;

- Rh3 Nh6;

- f5.

Boston now holds the superior position, despite the pawn deficit.

31…Ba5

32. e6 f6

- Kf1 Bb4;

- Bc1 Ke7;

- Bxh6 gxh6;

- Ke2 c3;

- Kd1;

- 37…c2+ (The bold advancement of this pawn and the subsequent threat to White make this position notably intriguing.);

- 38. Kc1 Rc4;

- Re3 Ba5;

- f3 Bb6;

- Re2 Rxa4;

- Rxc2 Ra5;

- Kd1 Rxf5;

- Ke2 Kxe6;

- Rc4 Rf4;

- Nc5+ Kf5;

- Ne4 a5;

- Rc6 Ke5;

- Rc3 f5;

- Nd2 Kd5.

The game concludes with a victory for Springfield, with a final position of 0-1.

Victorian Chess in the Age of Telegraphy

In the years that followed, telegraph chess evolved from single-game consultations to full-fledged telegraph match play. An exciting milestone occurred in February 1871 when a seven-board chess match was contested between teams in Sydney and Melbourne, separated by half the globe. In this match, the Sydney players experienced a 3-1 loss with three draws, showcasing the global reach of telegraph chess. However, another match would soon demonstrate Sydney’s prowess. This second encounter, described by Staunton, featured two teams, each with seven players who played individual games. The Sydney team, led by the Rev. J. Pendrill and featuring talents like Messrs. F.J. Gibbs, C.Y. Heydon, and others, faced off against opponents from the other side, including players such as A.H. Beyer and W.J. Fullerton.

The match was scheduled to start on May 24, 1869, coinciding with Queen Victoria’s fiftieth birthday. Unfortunately, due to the unpredictable weather conditions in the colony, the match faced multiple delays and even suspension for a few days. Nonetheless, Sydney eventually celebrated a belated victory in honor of Her Majesty, with a final score of 5-1 and one draw.

Staunton, while not providing specific game details, marveled at the incredible distances covered in this telegraph match. Given the approximately 1,500-mile separation between Sydney and Adelaide, where every move had to be transmitted twice, the chess pieces traveled a total of 3,000 miles per move. Remarkably, some moves took less than three minutes to travel between the cities. In the case of the longest game lasting 74 moves, the chess moves collectively traveled a staggering 220,000 miles—an astronomical feat, considering that the distance from Earth to the Moon at its closest point (perigee) is only 225,744 miles.

In a more down-to-earth development, but certainly important for the players involved, two additional telegraph chess games were published by Staunton in April 1873. These matches featured two major Canadian cities and marked the need for addressing cheating concerns in telegraph chess match rules. To address these issues, new rules were introduced, including four players at each board, a ban on assistance between boards, restrictions on consulting chess books, and no assistance from spectators or outsiders. Additionally, a time limit of ten minutes per move was enforced, and these alterations constituted the governing regulations as per the Canadian Chess Association. Staunton provided details about the players at board A, featuring Professor A.H. Howe, Messrs. H. von Bokum, J. Barry, and J.G. Ascher from Montreal, as well as Professor J.B. Cherriman, and Messrs. J.H. Gordon, G.L. Maddison, and G.H. Larminie from Toronto.

Montreal – Toronto [C62]

Telegraph Game, Board A – Early 1873

- e4 e5;

- Nf3 Nc6;

- Bb5 d6;

- Bxc6+ bxc6;

- 0-0 Nf6;

- Re1 Be7;

- c3 (Somewhat passive. Playing 7.d4 would have been more dynamic.);

7…0-0

- d4 Bg4;

- dxe5 Bxf3;

- Qxf3 dxe5;

- Bg5 Nd7;

- Bxe7 Qxe7;

- Qe2 Rfd8;

- Na3 a5;

- Rad1 Qc5;

- Rd2 Nb6;

- Red1 Rd6;

- Kf1 f6;

- Rd3 (This move appears to be a time-waster. Its purpose is not clear.);

19…Rad8

- f3 Kf8;

- R1d2 Ke7;

- h3 Na4;

- Rxd6 Rxd6;

- Qf2 (Another ambiguous move. Why not save the pawn by playing Nb1?);

24…Qxf2+

- Rxf2 Rd1+;

- Ke2 Nxb2;

- Nc4 Rb1;

- Nxb2 (Taking the a-pawn would have been risky as their opponents could have responded effectively with …Nd1.);

28…Rxb2+

- Ke3 Rb1;

- Kd3 g6;

- Rd2 (Very well played.);

31…a4

- Kc2 Rb5;

- c4 Rb4;

- Kc3 Rb6;

- Rb2;

Kd6 (It was later revealed that they should have exchanged the Rooks.)

- Rxb6 cxb6;

- Kb4 Kc7;

- Kxa4 Kb7;

- Kb4 Ka6;

- h4 f5;

- g4 fxg4;

- fxg4 h6;

- g5 h5;

- a3 Kb7;

- a4 Ka6;

- c5 b5;

- axb5+ cxb5;

- c6 (1-0).

At this board, Professor W. Hicks and Messrs. T. Workman, W. Atkinson, and J. White played for Montreal, while Messrs. F.T. Jones, H. Northcote, J. Young, and W. Dye represented Toronto. Toronto moved first with the Black pieces, and the game has been presented in standard notation.

Toronto – Montreal [C01]

Telegraph Game, Board B – Early 1873

- e4 e6;

- d4 d5;

- Nc3 Bb4;

- exd5 exd5;

- Bd3 Nf6;

- Nge2 0-0;

- 0-0 h6;

- Ng3 Bxc3;

- bxc3 Nc6;

- Re1 Be6;

- h3 a6 (Comparatively ineffective, giving Toronto an advantage in position.);

- Qf3 b5 (Another move with limited impact.);

- a3 Nh7;

- Qh5 Nf6;

- Qh4 Nh7;

- Qf4 Rc8 (This move presents an opportunity for their opponents to advance the a-pawn. A safer defense would have been 16…Ra7.);

- a4 Rb8;

- axb5 axb5;

- Ra6 (A challenging move to counter.);

19…Qd7

- Nf5 (Threatening to win a clear piece.);

20…Ne7

- Nxg7 (More effective and artistic than capturing the knight and then playing Ba3.);

21…Ng5

- Qf6 Ne4;

- Bxe4 dxe4;

- Nh5 Nf5;

- Rxe4;

- 25…Qd8 (The Toronto players announced mate in five moves at this point.);

- 1-0 (One attractive variation involves 26.Rg4+ Kh7 27.Qxf5+ Kh8, and so on, leading to mate. -JSH).

In this match, the Toronto team achieved victory, and the game has been presented in standard notation.

Conclusion

Staunton passed away on June 22, 1874, just a bit over a year after the games mentioned were published. He never witnessed the iconic Anglo-American Cable Matches held between 1895 and 1911. However, it’s plausible to believe that he would have endorsed the series, seeing it as a contest between some of the finest players from both nations. He would likely have celebrated when, in 1911, the Great Britain team clinched their third consecutive win, securing the silver Newnes Cup presented by Sir George Newnes earlier. The fervor the Cable Match competition stirred within the chess community would probably have been seen by Staunton as vindication of his early enthusiasm for chess via electric telegraph.